A brief history of Iraq from WWI to today

Estimated read time: 25-30 minutes (7,000 words)

Table of Contents

— Chapter I. A line in the sand

— Chapter II. A Hashemite Kingdom

— Chapter III. The rise of Baʿathism

— Chapter IV. At war with Iran

— Chapter V. The Gulf War

— Chapter VI. Saddam’s last dance

— Chapter VII. Rise and fall of the Islamic State

— Chapter VIII. Iraq today

The mountaintop in sight at last, Musa ibn Nusayr perseveres through the final ascent, each stride drawn from him as though the mountain itself resisted his passage. After one last push, the horizon opens up before him in a single, vast sweep. He looks down upon the desert below. His gaze drifts across the scorched horizon, lulled by the gentle rolling of the desert dunes endlessly folding in upon themselves, like the lines of an unremembering melody. But as his eyes continue east, the rhythm is suddenly broken, its soothing undulation violently thrusted aside by majestic brass walls rising from the golden sand. The walls wrap a vast city, one of unbeheld beauty, a seemingly timeless presence basking in the desert sun. Cautiously, ibn Nusayr approaches the city gates; there, he finds a set of tablets carved from white marble. Like an echo drifting silently through the desert, a warning is engraved upon them:

Oh son of Adam, how heedless are you of that which is before you! Do you not see that the cup of death is already poured for you, and that soon you must drain it to its dregs? Where are those who ruled over the lands and who humbled God’s servants and led great armies — where are they now? By God, the one who destroys all joy and scatters every gathering — he came down upon them, and transported them from their spacious palaces to the narrow chamber of the grave.

Every empire believes itself immortal — until it is no more. Looking back at the last century of Iraqi history, one inevitably concludes that the warning uncovered by Musa ibn Nusayr in The Thousand and One Nights on the caducity of eternal glory has gone largely unheeded by successive rulers in Baghdad. In the 1980s, Saddam Hussein carved his name into the ruins of Babylon, inscribing it alongside those of Nebuchadnezzar II and the other great Mesopotamian kings, as if to outlast time. Today, a blanket of dust softens the marble floors of his abandoned palaces. The once-imposing walls are overtaken by a riot of graffiti, creeping upwards like roots nourishing the wooden reliefs of date palms and pomegranate trees. Saddam’s name has long been scraped away. His dream of eternal glory lies broken, scattered amongst the palaces he built to house it.

In its mythomaniacal pursuit of eternal power, Saddam’s regime has become little more than another cautionary tale. Not altogether dissimilar to ibn Nusayr’s legendary expedition, the foreign forces which occupied Iraq following Saddam’s removal from power have seemingly fallen for the same illusion, failing to understand the writing on the wall and choosing to blindly exploit the country’s resources instead. That of the city of brass is not a tale — it is a mirror, and one which Baghdad has looked into more than once.

Present-day Iraq is but the final page in a millennia-old chronicle, and to begin to understand its complexities, we must at least turn back a hundred years into its layered and turbulent past.

Chapter I. A line in the sand

At the dawn of the 20th century, the ancient land of Mesopotamia stands as a shadow of its former glory, the enchanting Baghdad of The Thousand and One Nights now little more than a romantic dream from a millennium past. Decades of ill-governance by the waning Ottoman Empire — by now, the prototypical ‘sick man of Europe’ — have left the three vilayets [provinces] of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul with underdeveloped agricultural economies and largely tribal societies. Yet, the barren sands once trodden by Gilgamesh in his quest for immortality conceal a secret older than the legendary king of Uruq himself: vast oilfields stretch from the northern plains of Mosul down to the warm waters of the Persian Gulf, buried no deeper than a few thousand metres underground. Unsurprisingly, the Western powers have their sights set on the Ottoman province and its untapped riches.

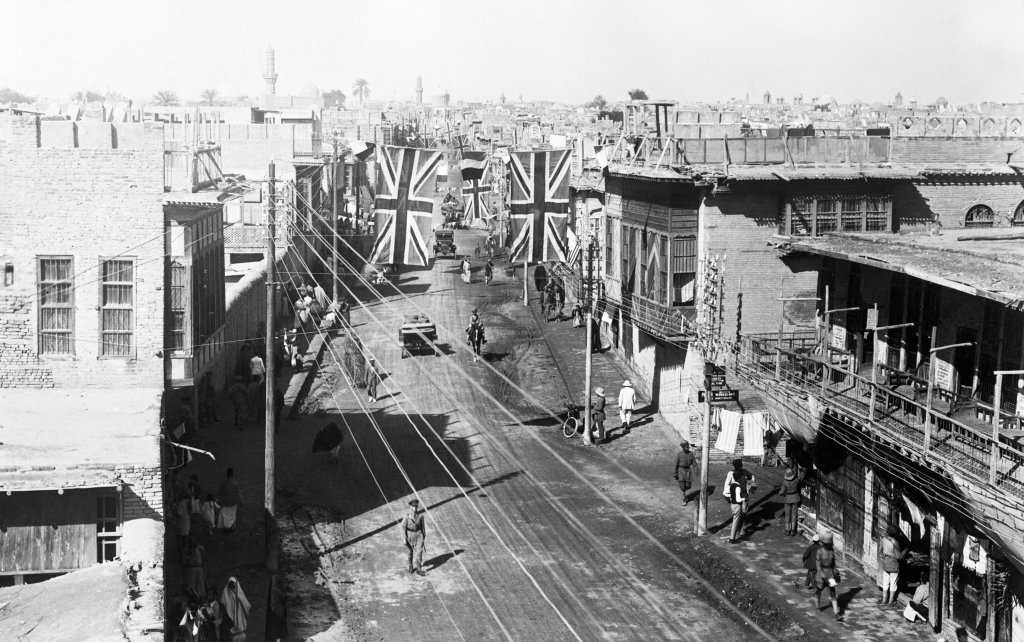

By the turn of the century, Britain has firmly established itself as the dominant Western power in the Middle East. It exerts an increasingly hegemonic influence over Persia — a key theatre in the ‘Great Game’ against the Russian Empire — and has woven an intricate network of colonies, protectorates, and suzerainties throughout the Arabian Peninsula and its surroundings. In Mesopotamia itself, however, British intervention initially remains limited to the establishment of a small diplomatic and commercial presence. This changes dramatically with the onset of World War I, as an Anglo-Indian expedition lands in Mesopotamia, swiftly seizing the vilayet of Basra from Ottoman control and then marching north towards Baghdad. Concurrently, British forces capture Jerusalem and, joining efforts with the Arab Revolt ignited by the Hashemites in the Hejaz, drive the Ottomans out of Syria. After six centuries, the sun sets on the Ottoman Empire for the final time.

As the Ottoman Empire lies defeated in the ashes of World War I, its vast territories are up for grabs. In the aftermath of the 1918 armistice signed at Mudros, Mesopotamia initially falls under Anglo-Indian administration. This provision is formalised a few years later, when Britain and France announce a series of League of Nations Mandates. Their strategy is rooted in the secretive Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 — a clandestine deal which sees the two European powers carve up the Middle East: Palestine and Iraq become British mandates, while Syria and Lebanon are awarded to the French.

‘‘With regard to the Vilayets of Baghdad and Basra, the Arabs will recognise that the established position and interests of Great Britain necessitate special measures of administrative control in order to secure these territories from foreign aggression, to promote the welfare of the local populations and to safeguard our mutual economic interests.’’

British High commissioner Sir Henry McMahon to the sharif of mecca, 1915

As revealing as what the Mandate provisions do include is what they so conspicuously omit. In the first place, the sheikhdom of Kuwait. Its initial recognition, on the eve of World War I, as an autonomous kaza [district] of the Ottoman Empire effectively severs it from the rest of Mesopotamia, establishing its basis for formal independence. Secretly, however, the sheikdom falls under British suzerainty, with the ruling House of Sabah effectively subordinated to British authority in all external affairs. The arrangement reflects the principles of the forward school dominating British foreign policy and aimed at proactively expanding influence in the region to protect shipping routes to India. In return, Britain safeguards Kuwait’s borders from the Ikhwan raids emanating from the Nejd Sultanate, soon to evolve into present-day Saudi Arabia.

The map is redrawn, and the seeds for future turmoil are sown.

Equally absent from the post-war provisions is a separate state for the Kurds — an Iranic people numbering in the tens of millions. While the 1920 treaty signed by the Allied Powers and the Ottomans in Sèvres provides for an independent Kurdistan, the Turkish civil war it ignites means the agreement is never ratified. In its aftermath, the Kurds are left stateless and scattered across northern Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey.

Kuwait’s secession from Basra and the struggle for Kurdish independence would have a profound impact on the region’s destiny throughout the 20th century. The map is redrawn, and the seeds for future turmoil are sown.

Chapter II. A Hashemite Kingdom

Discontent towards the British rule simmers swiftly beneath the unyielding Mesopotamian sun, and in 1920, Baghdad rises at once. The revolt is intense, bloody, and costly, forcing Britain to reconsider its grip on the region and pivot in favour of a more indirect control. At the Cairo Conference of 1921, orchestrated by Winston Churchill, the Sharifian solution emerges. The Hashemite royal Faisal, who led the Arab Revolt against the Turks only to be ousted from Syria by the French, is installed as the King of Iraq. It is a calculated move — a monarchy that appears independent but keeps British interests secure behind the throne, while also finely balancing the Hashemite demands following their role in WWI with the French territorial aspirations.

King Faisal I inherits deep-seated sectarian divisions, with the Shia majority pitted against the large and politically dominant Sunni minority at least since the Safavid-Ottoman conflicts centuries before. Other Iraqi minorities include Muslim and Yazidi Kurds, Muslim Iraqi Turkmen, and Syriac Christian Assyrians. In spite of this delicate ethnological balance, the Iraqi Kingdom is perhaps one of the more stable mandates in the Middle East, with King Faisal emerging as a unifying force.

Over the course of Faisal’s reign, Western powers tighten their hold on Iraq’s valuable resources. In 1926, a young Kemalist Turkish republic relinquishes its claims over the oil-rich city of Mosul; shares of the Iraq Petroleum Company are then redistributed amongst Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States.

The British trusteeship over Iraq is a Class A mandate, meaning that full independence is deemed feasible in the near future. Indeed, in 1930, an agreement is reached to end the British occupation. Two years later, Iraq is formally independent and joins the League of Nations under British sponsorship, stepping onto the global stage.

Following King Faisal’s untimely death, tensions begin to rise once again between the civilian government and the military, culminating in an ultimately unsuccessful revolt in 1936. While the rebellion is short-lived, it is of symbolic importance, as it marks the first modern coup d’état in the Arab world, and in many ways, the beginning of the end for Iraq’s constitutional order.

As World War II engulfs the globe, the Middle East becomes a strategic hotspot. In 1941, with British forces stretched thin fighting Nazi advances in North Africa, a pro-Axis government seizes power in Baghdad. Rashid Ali al-Gaylani’s putsch threatens Allied control of the region. Britain responds swiftly, invading and occupying Iraq, and reinstating the pro-British Hashemite monarchy. The ensuing eight terms of prime minister Nuri al-Said see the British further cement their influence over the country. Eventually, Iraq joins the Baghdad Pact, a military alliance with the UK aimed at containing Soviet expansion, and supports both the British invasion during the Suez Crisis and the pro-Western Maronite government in the Lebanese civil war.

Chapter III. The rise of Baʿathism

The growing Western influence in Baghdad clashes with the desert winds of Arab nationalism blowing over from Nasser’s post-Pharaonist Egypt. Frustration with Western dominance over the Arab world is further exacerbated by the Zionist ambitions in Palestine. It is against this backdrop that the pan-Arabist Baʿath Party — founded in a coffee shop in 1940s Damascus by an Orthodox Christian teacher — gathers pace. The movement promotes a pan-Arabist ideology rooted in secularism and socialism, and finds fertile ground in the Fertile Crescent.

In Baghdad, an ideologically heterogeneous coalition of pan-Arabists and Iraqi nationalists hastily assembles to counter the pro-Western government. Finally, on July 14, 1958, a thunderclap of revolution rattles the skies over Baghdad. Brigadier Qasim and Colonel Arif lead a military coup, toppling the Hashemite monarchy in a blaze of gunfire and ambition. The new republic withdraws from the Baghdad Pact, shaking off the Western chains. Tensions, however, grow rapidly between Qasim, an Iraqi nationalist with communist support, and the socialist pan-Arabists of the Baʿath party. Arif is arrested, and hostility towards Egypt mounts.

Five years after the coup, and with probable U.S. involvement, the pan-Arabists are led by Arif into the Ramadan Revolution; Qasim is overthrown and executed. Yet, the revolutionary government is short-lived: the collapse of the United Arab Republic between Egypt and the Syrian branch of the Baʿath party causes an almost immediate rift in Baghdad between the Nasserists and the increasingly violent Iraqi Baʿath party. Later that year, Arif leads a second coup, purging all Baʿathist elements from his Nasserist government.

The rapid succession of armed rebellions that takes place in Iraq in the late ’50s and into the ’60s reflects the typical struggle of a country that, having just unbound itself from the oppressive grip of neocolonialism, attempts to define the kind of nation it seeks to become. Yet, the speed and the violence of this transition hint at deeper fractions — deferred rather than resolved — amongst a constellation of entities seemingly unwilling to set aside their differences for the sake of their nation’s future.

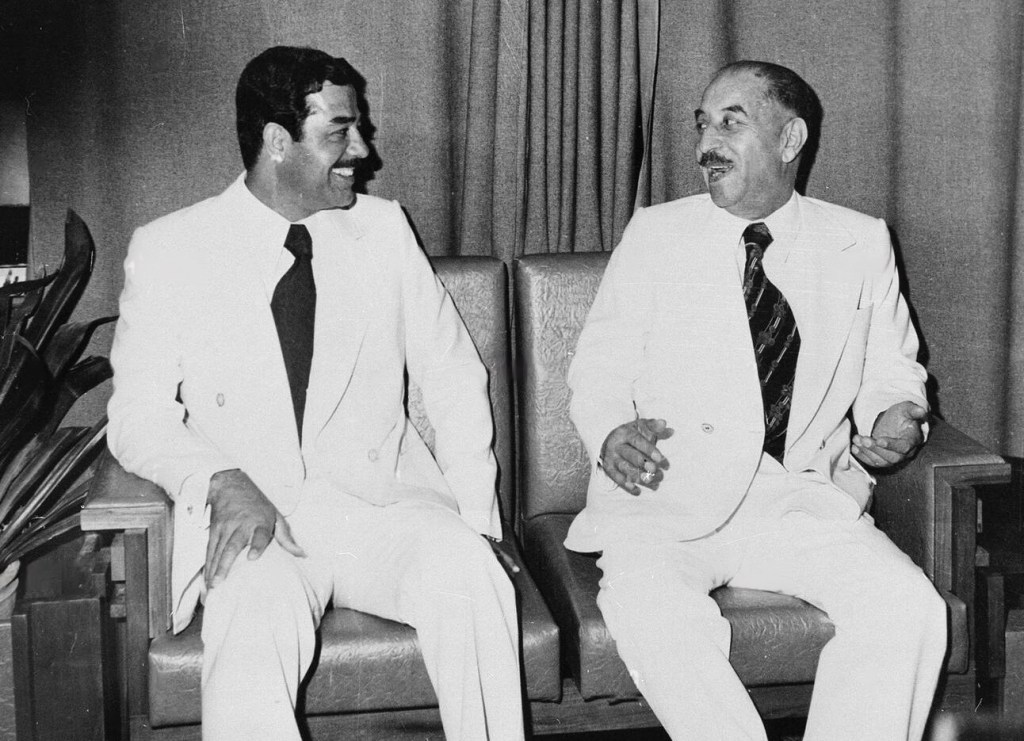

In any case, the Iraqi Baʿath party, a primarily Sunni movement — albeit officially secular — in Shia-dominated Iraq, is momentarily relegated to the shadows of Baghdad’s souks. That is, until the Arab catastrophe of the Six-Day War against Israel profoundly shakes the Middle East, intensifying anti-Western sentiments and irredeemably tainting Nasser’s image. The Iraqi Baʿath party seizes the moment, and in 1968 it carries out a bloodless coup, taking over the country. Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr becomes president, with his deputy a young Saddam Hussein.

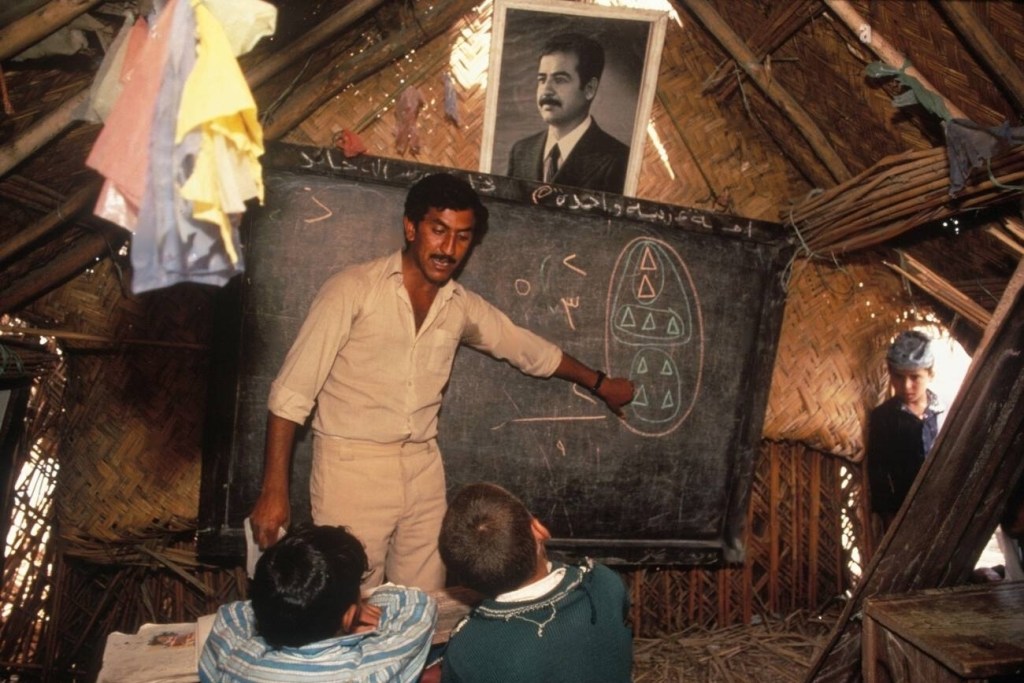

By the mid-1970s, Saddam is the de facto dictator of Iraq. Everyday life under Saddam’s iron fist is a paradox of burgeoning opportunities and suffocating suppressions of basic liberties. His secret police silences dissent through intimidation, imprisonment, torture, ethnic cleansing, and forced disappearances. At the same time, Iraq develops a sophisticated free and universal healthcare system, women and men are declared equal before the law — significantly boosting women participation in the workforce — and literacy rates vastly improve as education is made free and mandatory.

In the mountainous north, another struggle unfolds. The Kurds — an Iranic people yearning for a homeland — clash with Baghdad. Their promised autonomy in 1970 is shattered by Saddam as he instead consolidates power and launches an aggressive Arabisation campaign in the region. The Kurds rise again, bolstered by significant support from Imperial Iran and its U.S. and Israeli allies. Through the Algiers Agreement, Iraq manages to avoid a full-scale war against the superior Iranian army. Saddam, however, is forced to offer significant territorial concessions, including shared control over the crucial Shatt al-Arab waterway, in exchange for Tehran withdrawing its support for the Kurds. Betrayed and isolated, the Kurdish resistance collapses. Persecution of the Kurds intensifies; their hopes for freedom crushed under the heel of Saddam’s regime.

Between puffs of his Cuban cigar, he calmly reads out some 70 names.

The retrospective humiliation of the Algiers Agreement is short-lived, as Saddam boldly nationalises the oil industry in 1972, freeing Iraq from foreign oil companies. The following year, an OPEC embargo during the Yom Kippur war causes oil prices to quadruple, boosting Saddam’s domestic popularity and fuelling his grandiose ambitions.

In 1979, al-Bakr finally cedes power to Saddam in mysterious circumstances. Six days into his presidency, Saddam summons an emergency meeting of the Baʿath party elite. As the temperature outside the hall soars to a sweltering 48°C, he stands unflinchingly at a wooden podium, the red velvet drapes pouring down behind him like blood from the heavens. Between puffs of his Cuban cigar, he calmly reads out some 70 names. As each man stands, they are escorted out by Saddam’s guards. Half are imprisoned, the others are executed. Saddam’s regime has officially begun.

Chapter IV. At war with Iran

In 1979, the Shia Revolution engulfs neighbouring Iran, marking a dramatic shift in the relations between Baghdad and Tehran. Iran now represents a major threat, with the Ayatollah explicitly encouraging Iraq’s Shia majority to rise against Saddam’s Sunni rule. On the other hand, the Shia Revolution scrambles Iran’s external relations, forcing even long-standing allies such as the U.S. and Israel to reassess their ties with Tehran. This restructuring affords Saddam an unanticipated opportunity to establish himself as the main actor in the Persian Gulf. The die is cast: in 1980, Saddam invades Iran.

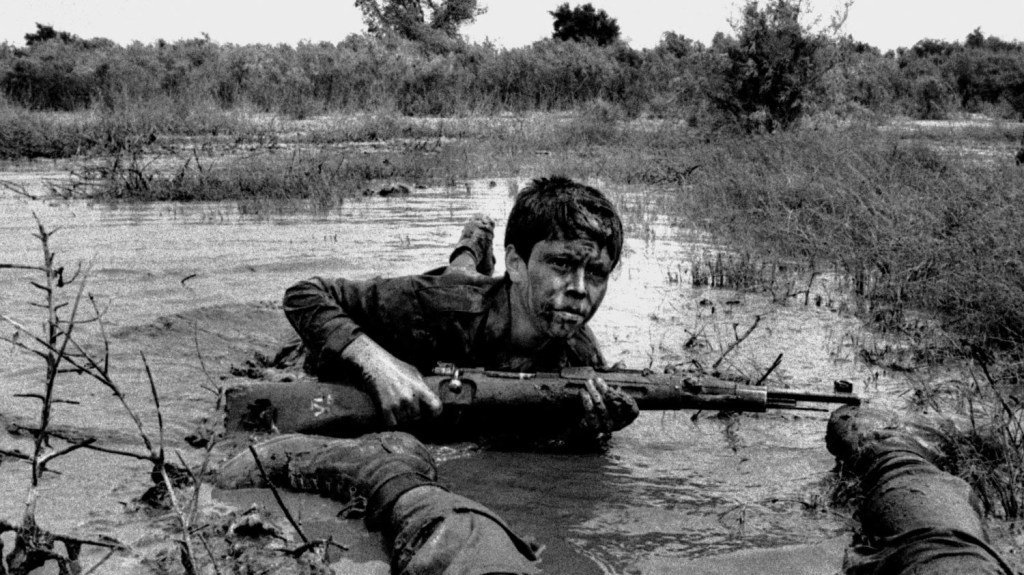

The Iran-Iraq War is a brutal stalemate marked by trench warfare, missile exchanges, and immense human suffering. The U.S. and the Gulf Arab states publicly support Iraq, fearing the spread of Iran’s Islamic revolutionary ideology; so does the Soviet Union, as it struggles to contain the fading of its influence in Central Asia. Rather than expressing genuine support for Saddam, however, officials in Washington are primarily concerned with preventing an outright Iranian victory — the prevailing, unspoken desire being to see both sides bleed each other dry.

‘‘It is a pity both sides can’t lose.’’

[ATTRIBUTED TO] HENRY KISSINGER, former u.s. secretary of state

Indeed, at various points in the conflict, both the Americans and the Soviets also engage in some level of support to Iran, as to maintain a balance of power between the two belligerents. The infamous Iran-Contra affair, for instance, exposes clandestine arms sales to Iran by high-ranking officials in the Reagan administration, facilitated through Israeli backchannels. Israel’s covert mediation is aimed at reviving the ties with Tehran severed by the fall of the shah — and in Baghdad, it undoubtedly rekindles the memory of the Ridda apostasy wars, when Arabian Jews and Persians joined forces in support of the ancient rebellion against the early Arab caliphate. Another close ally of Tehran is the Shia Alawite President of Syria, Hafez al-Assad. The seemingly paradoxical friendship between pan-Islamic Iran and secular Arab nationalist Syria, born out of the common rivalry with the Iraqi Baʿath party, is perhaps one of the longest-lasting effects of the Iran-Iraq conflict on the Middle Eastern geopolitical balance.

‘‘Since weapons have become more valuable as the war drags on, then we have the right to be suspicious of the American call to stop the war. […] There is a Zionist desire for the war to halt, but not to end; and this is true even among some of the people in the nations of this region.’’

SADDAM HUSSEIN TO HIS INNER CIRCLE, 1986

‘‘Americans like Iranians more than us, and most powerful nations also like them more than us. However, they do not like them because they are nicer than us or because they are better than we are. They only like Iranians because they can be pulled from the street into a car easily, unlike us.’’

During the Iran-Iraq war, both countries target oil shipping routes, leading to significant international efforts to protect global oil flow. The conflict oscillates repeatedly between a ‘tanker war’ and a ‘war of the cities’, with bombing campaigns reaching both capitals, Tehran and Baghdad. Shia rebellions within Iraq are repressed with violence; following an attempt on his life, Saddam orders the execution of 150 Dawa party rebels in the town of Dujail alone.

In 1987, the Iraqi air force unleashes chemical weapons against the Kurdish resistance forces loosely aligned with Tehran. These massacres are met with little condemnation in the West — the human rights violations overshadowed by the desire to see Iran defeated. Later reports would uncover the brutal realpolitik at work — the U.S. and its allies revealed to have supplied key military intelligence and allowed the exportation of dual-use biological agents such as anthrax to Iraq despite full knowledge of Saddam’s intentions of waging chemical warfare.

Nothing gained, everything lost.

In 1988, after hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, Iraq and Iran agree to a UN-mediated paix blanche, essentially returning to the pre-war status quo — nothing gained, everything lost.

Chapter V. The Gulf War

Emerging from war, Iraq is economically crippled. Unable to repay the war debts he owes to the Gulf Arab nations, Saddam accuses Kuwait of economic warfare over oil prices — specifically, of having exceeded the OPEC quotas. Compounding this economic strife is Iraq’s desire to extend its very limited seafront, measuring a mere 60 km along the Persian Gulf, and secure better port access. Saddam’s economic and strategic urgency further intertwines with the long-held belief that Kuwait’s 1913 secession had been an illegitimate act — a lingering injustice orchestrated by the British Empire. Amidst ambiguous signals from Washington regarding the border dispute, Saddam’s mind is set. In August 1990, Iraqi troops march into Kuwait and swiftly annex the country.

[Regarding Kuwait’s 1913 secession from Basra] ‘‘Was it legal for this part of Iraq to have been severed in 1913? Was it in accordance with the law? […] The return of Kuwait to the fold of its motherland, from which it was long severed and usurped like an infant separated from its mother, will further strengthen Iraq in its endeavour to re-assert its role on the pan-Arab level.’’

Saddam hussein

[Regarding Kuwait’s alleged economic warfare] ‘‘The former rulers of Kuwait knew what to do as to harm their rivals — as merchants themselves, they are good at blackmail, exploitation, and destroying their opponent.’’

With control over Kuwait, Saddam now commands 15% of the world’s oil reserves and poses a direct threat to the additional 15% located just across the border in Saudi Arabia. The prospect of Saddam controlling such a vast portion of global oil supplies alarms the international community. A formidable coalition, led by the United States, forms to confront him and protect the stability of global oil markets.

Operation Desert Shield amasses troops in Saudi Arabia, morphing into Operation Desert Storm in early 1991. A relentless bombing campaign decimates Iraqi infrastructure. In a desperate gambit, Saddam launches missiles at Israel, hoping to fracture the coalition, but Israel does not retaliate. The coalition’s ground assault is swift; Kuwait is liberated by the end of February. Defeated, Iraq accepts the UN terms.

‘‘This conflict started August 2nd, when the dictator of Iraq invaded a small and helpless neighbour. Tonight, the battle has been joined.’’

George H. W. BUSH DECLARING WAR TO IRAQ

But the victory is hollow. Saddam remains in power — his regime intact but his nation shattered, now facing even higher debts and stricter sanctions. The U.S. and UK repeatedly veto UN proposals to ease the ever tighter measures against Baghdad. Inflation soars by thousands of percentage points, the majority of the population verges on starvation, and embargoes on basic chemicals needed for sewage treatment trigger devastating cholera and typhoid outbreaks. The UN’s own estimates place the number of preventable civilian deaths caused by the sanctions at around one million. Textbooks and journals are banned, in what UN aid agencies describe as an ‘intellectual genocide’; even pencils are outlawed, to prevent their graphite cores from ending up as fuel for clandestine nuclear reactors. In 1996, Iraq is eventually allowed to sell limited amounts of oil to purchase food and medicines under the Oil-for-Food Program.

[Question:] ‘‘We have heard that half a million [Iraqi] children have died [due to sanctions against Iraq]. That’s more than the children who died in Hiroshima. Is the price worth it?’’

U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE ALBRIGHT

[Answer:] ‘‘I think it is a very hard choice — but we think the price is worth it.’’

The UN periodically sends inspectors to verify and enforce the progress of the Iraqi nuclear, chemical and biological disarmament. These visits are not without difficulties, as Saddam often resorts to heavy negotiations, with the U.S. and the UK occasionally turning to direct military intervention, as is the case in the 1998 Operation Desert Fox ordered by President Clinton. An unhoped-for source of intelligence for the UN’s inspection programme is Saddam’s own son-in-law, Hussein Kamel Hassan, who defects to Jordan in 1995 and reveals extensive details about Iraq’s weapons industry. The following year, lured by Saddam’s promise of amnesty, Hussein Kamel drives back to Baghdad. Three days later, Iraqi state television broadcasts footage of his bloodstained corpse.

But the victory is hollow.

Exploiting Iraq’s apparent military weakness, the Kurds in the north and Shia in the south rise up, encouraged by the U.S. but ultimately left unsupported. Despite Saddam’s brutal repression, the Kurds manage to carve out a semi-autonomous region, protected by Western-enforced no-fly zones. Unity, however, proves elusive, as fierce rivalries erupt between the Iran-backed and socialist-leaning Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), especially popular amongst the southern intellectual and urban milieu, and the Turkey-armed Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), which draws significant support from the more traditional and conservative northern tribes. This intestine conflict intertwines with Turkey’s CIA-backed campaign against the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK). The Kurdish internecine war rages on until a U.S.-brokered truce in 1998 reunites the Kurdish region under a fragile but hopeful autonomy — though not before Saddam’s tanks, seizing a window of opportunity, roll unhindered up to the Kurdish parliament in Erbil, forcing the CIA to flee its Kurdish safe haven.

The pauperisation of Iraq by the West, aimed perhaps at encouraging a regime change from within, backfires in a spectacular fashion. A sense of national consciousness is revived, and the middle class — once the most likely source of a coup — is reduced to poverty and dispersed into the countryside. Saddam’s control over food rations allows him to strengthen his personality cult, even amongst the Shia minority. Dozens of lavish presidential palaces spring up throughout the country, thousands of full-body monuments of Saddam look upon his people, and textbooks dogmatically depict him as a fatherly figure. The increased aggressiveness of the UN mission, now an unapologetic instrument of Western intelligence, isolates the U.S. and the UK from France, China, and Russia, with the latter pushing for a significant lifting of Iraq’s oil sales restrictions. While the UN fractures under the weight of competing interests, the Iraqi people are more united than ever, galvanised by the very measures intended to break them.

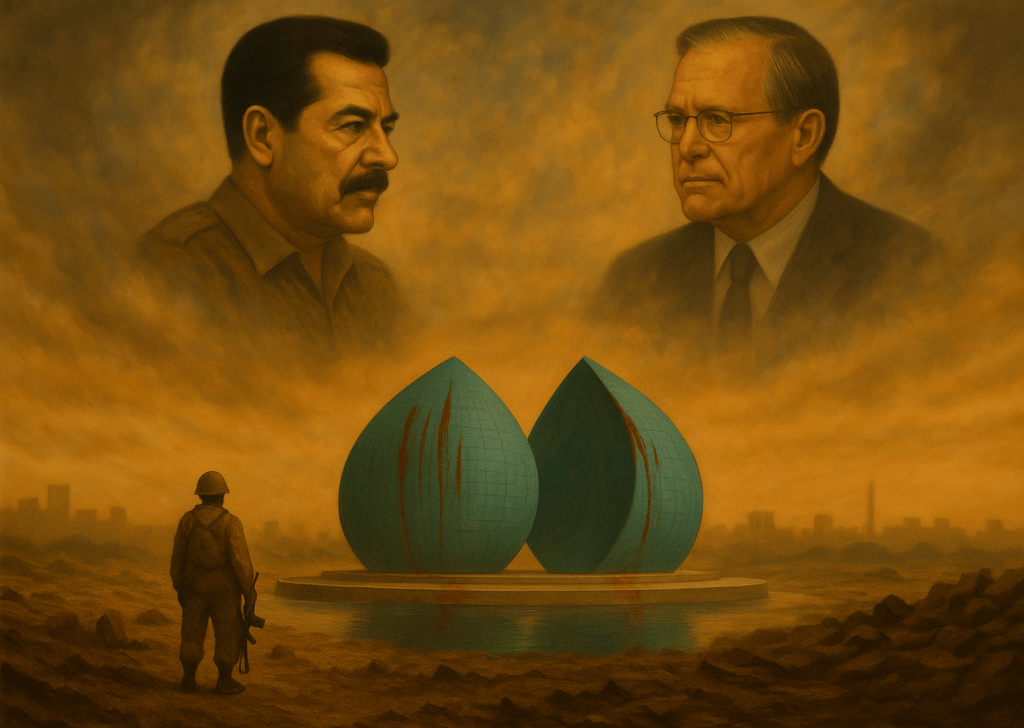

Chapter VI. Saddam’s last dance

The dawn of the new millennium brings a new American presidency and a new crisis. After the shock of the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush targets Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as constituting an ‘Axis of Evil.’ Iraq, in particular, is accused of state sponsorship of al-Qaeda’s terrorist activities and of non-compliance with UN security inspections. This lack of cooperation leads to the belief that Iraq hides weapons of mass destruction. From the U.S. administration’s perspective, this suspicion rationalises a doctrine of preventive war, justifying U.S. military intervention even without an explicit attack from Iraq and without UN support.

‘‘As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.’’

U.S. SECRETARY OF DEFENSE DONALD RUMSFELD IN PRESS CONFERENCES

[Reporter:] ‘‘Is [a direct link between Baghdad and terrorist organisations] an unknown unknown?’’

‘‘I’m not gonna say which it is.’’ [smiles]

[Reporter:] ‘‘Iraq stated yesterday that they have no weapons of mass destruction.’’

‘‘They’re lying. They have them and they continue to develop them. They’ve had an active program to develop nuclear weapons, they’re actively developing biological weapons. I don’t know what other kind of weapons would fall under the rubric of weapons of mass destruction, but if there are more, I suspect they are working on them as well.’’

The U.S. administration’s stance is rooted in neoconservative ideology, which identifies in the Middle Eastern security regimes the cause of, rather than a potential solution to, the global jihad movement. Iraq, in particular, is singled out as an appropriate starting point for regional change, and after the fall of Kabul, the Bush administration indeed sets its sights on Baghdad.

In March 2003, after Iraq’s failure to comply with a final UN Security Council Resolution, the U.S. — opposed by France, Germany, Russia, and China — leads a ‘‘coalition of the willing’’ to invade Iraq through Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. A massive aerial bombing campaign accompanies a ground invasion. UK forces besiege and eventually capture the Basra oil fields in the south, while the U.S. advances north toward Baghdad, fighting battles at Nasiriyah and Najaf. Troops are also deployed in the northern regions with the help of Kurdish allies. Just ten days into the war, U.S. troops take Baghdad. Saddam Hussein’s regime is history, his grand palaces as lifeless and desolated as the city of brass in The Thousand and One Nights.

‘‘Iraqi denials of supporting terrorism take their place alongside the other Iraqi denials of weapons of mass destruction — it is all a web of lies.’’

u.s. Secretary of state colin powell to the u.n.

But the promised liberation soon descends into chaos, as the U.S.-led Coalition Provisional Authority suppresses local elections and lacks a clear plan for nation-building. The pursued policy of de-Baʿathification sees the dismissal of hundreds of thousands of military personnel, who are left in the streets armed, unemployed, and disgruntled. The deep power and security vacua create a fertile ground for non-state and transnational insurgent actors.

‘‘Let me begin by saying, we were almost all wrong […] it is highly unlikely that there were large stockpiles of deployed militarised chemical and biological weapons [in Iraq].’’

U.S. WEAPONS INSPECTOR DAVID KAY

Meanwhile, the CIA’s exhaustive search for usable weapons of mass destruction returns empty-handed, unravelling the rationale which the invasion had been waged on. Furthermore, as the American occupation drags on, horrific evidence of war crimes committed by the U.S. Army and the CIA emerges. The war’s justifications crumble further beneath revelations of prisoner torture at Abu Ghraib, sexual violence, and civilian massacres.

As the day breaks over Baghdad, a gallows’ floor drops, and four decades of Iraqi history swing lifeless from a noose.

Saddam Hussein is eventually found crouching in a small pit in the ground some 150 kilometres northwest of Baghdad. After spending a few years in U.S. detention, he is tried by an interim Iraqi government, found guilty of crimes against humanity in relation to the Dujail massacre, and unceremoniously executed on a cold December morning. As the day breaks over Baghdad, a gallows’ floor drops, and four decades of Iraqi history swing lifeless from a noose.

Chapter VII. Rise and fall of the Islamic State

The fall of Saddam’s regime sees Iraq’s long-repressed Shia majority step into power. Its ascent is led by the Iranian-born Grand Ayatollah Sistani; the U.S. Coalition Provisional Authority swiftly dissolves and hands over power to an unelected interim government. Sistani, a quietist Shia cleric, promotes Iraq’s first parliamentary elections in 2005, which result in the Shia coalition forming a transitional government. Shortly thereafter, intra-Shia tensions rise, as the Shia activist Sadrist movement, tied to Iraq’s most prominent clerical family, stages an uprising which is quelled by American and Iraqi troops.

The deep power and security vacua create a fertile ground for non-state and transnational insurgent actors.

The Sunni opposition initially consists of the poorly coordinated remnants of the Baʿathist establishment and Saddam loyalists. The escalating sectarian violence claims thousands of lives each month. While the Iraqi democratic model is applauded by other Shia-dominated countries, millions of Sunnis flee from Baghdad towards northern Iraq, where they are joined by foreign jihadi fighters. The Western occupation and the Shia political resurgence fuel a revival of militant fundamentalism to levels not seen in decades.

The U.S. killing of the Palestinian jihadi leader al-Zarqawi, founder of al-Qaeda in Iraq, accelerates the transition of the Sunni extremists’ resistance from disparate cells into an organised transnational militant network, the Islamic State of Iraq, in 2006.

The Sunni fundamentalists embrace jihadist Salafism, an ultra-conservative doctrine tracing its origins to the Wahhabi reformers of Saudi Arabia and aimed at establishing a global caliphate. The movement advocates a puritanical return to Islam’s origins — the practices of the first three generations of Muslims, known as the Salaf. This radical ideology endorses a violent interpretation of the ‘lesser jihad’ against perceived infidel targets, notably Shia Muslims, as a viable means to advance the Caliphate’s cause, and rejects the political structures associated with any kind of secular governance. The Islamic State in Iraq is a direct evolution of the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda, the organisation which emerged in the 1980s in the heart of the Afghan theatre as a network of anti-Soviet foreign mujahideen fighters — partly mobilised and supported by the CIA and Pakistan, and now finding fertile ground in post-invasion Iraq.

The 2011 withdrawal of the U.S. Army from Iraq, commanded by President Obama and precipitated by the failure to secure legal immunity for American troops, is predicated on a flawed assessment of the Iraqi forces’ ability to counter potential Islamist resurgences. Indeed, by 2013, the Islamic State of Iraq, now rebranded as ISIS or ISIL, re-emerges from Camp Bucca, near Basra, with brutal strength under its new leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, previously a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The rise of ISIS concurs with, not coincidentally, a period of heightened instability in and around Iraq. A civil war rages in Syria, tensions escalate between Baghdad and Kurdistan over oil revenue sharing and self-determination, and intra-Kurdish relations deteriorate. Sweeping reforms fail to curb the widespread corruption plaguing the Iraqi government. Sunni Iraqis — having largely set aside their insurgency to engage positively with the new political order — erupt in protests over claims of sectarian marginalisation at the hand of the central Shia-dominated cabinet, as al-Maliki of the Shia Dawa party retains his position as prime minister despite the 2010 electoral victory of the secular and non-sectarian al-Iraqiya bloc. The Awakening fighters, a pro-government paramilitary coalition of moderate Sunni tribes formed to fight al-Qaeda and then ISIS, are dismantled by the al-Maliki cabinet.

Amidst this turmoil, ISIS surges through predominantly Sunni northwestern Iraq. In 2014, its rebels seize control of the key cities of Fallujah, Ramadi and Mosul, as Iraqi security forces falter. Thousands are killed each month, hundreds of thousands flee, while others rejoice at their liberation from the central government. ISIS declares the establishment of a global Caliphate, the Islamic State, ninety years after Kemal Atatürk’s abolition of the last Caliph. The Western world recoils at the Islamic State’s barbarity from afar — beheadings, slavery, genocide — until the horror strikes much closer to home, with horrific attacks throughout the Western world.

Only four years after his meteoric rise, al-Baghdadi is a landless Caliph on the run.

The broad U.S.-led Operation Inherent Resolve forms to fight the Islamic State. Obama redeploys ground troops and organises airstrikes to support a humanitarian corridor for the evacuation of the Kurdish Yazidi minority. Iraqi forces consist mainly of state security units and state-sponsored Shia paramilitary mobilisation networks (PMF), fighting alongside local Sunni tribes. U.S.-funded Kurdish peshmerga forces are heavily involved in the fight against ISIS, but also capitalise on the Iraqi armed forces’ initial retreat to take control of the city of Kirkuk, outside the Kurdistan region. Iran, Iraq’s Shia ally, mobilises and arms Shia militias through its Revolutionary Guard, and issues a fatwa bolstering the fight against the Islamic State. Russia provides airstrike support against the Islamic State as well as private military contractors such as the Wagner Group, primarily in support of Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria. Turkey’s role is more complex, as it initially conducts operations against the PKK — the Kurdish militant group fighting ISIS — and fails to close the so-called ‘jihadi highway,’ its porous border with Syria crossed by foreign fighters to join the Islamic State. Eventually, after Islamic State attacks within its territory, Turkey shifts more decisively against al-Baghdadi’s caliphate.

‘‘Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is dead. He died like a dog, he died like a coward — whimpering and crying and screaming all the way.’’

U.S. PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP ANNOUNCING AL-BAGHDADI’S KILLING

In late 2015, the Coalition begins liberating Islamic State positions. Ramadi and Fallujah are retaken, and a gruelling 9-month siege of Mosul laid by the international coalition is finally successful in 2017. Iraqi forces storm Kirkuk, and in a matter of mere hours retake the city from the occupying Kurdish forces. Finally, in December of that year, Baghdad declares victory over the Islamic State. Only four years after his meteoric rise, al-Baghdadi is a landless Caliph on the run. He is eventually killed by a U.S. Special Forces raid in Syria in 2019.

Chapter VIII. Iraq today

The shift in power in Baghdad following the end of Saddam Hussein’s regime has led to a significant rapprochement between Iraq and Iran. As a result, Baghdad now finds itself caught in the crossfire of escalating tensions between Washington and Tehran — tensions deepened by Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal and the subsequent adoption of a ‘maximum pressure’ campaign against Iran. Whilst asymmetrical conflicts launched by non-state actors such as ISIS — whose ideology partially persists, despite its territorial control having crumbled — represent an enduring threat, to this day they are largely limited to sporadic and low-level insurgencies. Rather, it is foreign interference — particularly from Iran — which the U.S. primarily fears with respect to Iraq’s sovereignty.

In recent years, the Quds Force, the foreign arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, has expanded its presence in Iraq, often operating through Shiite proxies such as Kata’ib Hezbollah, a branch of the PMF, and pushing for the embedding of other Shiite paramilitary entities into Iraq’s formal security apparatus. This armed network is a core component of Iran’s Axis of Resistance, a Shiite power bloc aimed at countering U.S. and Israeli influence in the region.

Indeed, military and diplomatic coordination between Iran’s proxies in various countries appears to be increasingly systematic and institutionalised. Shared anti-Western, anti-Saudi, and anti-Israeli objectives now clearly take precedence over sectarian divides. Tehran provides support across ideological lines, backing groups from the Zaydi Shiite movement of the Houthis in Yemen to the Sunni Islamist organisation Hamas in Palestine. Iraq finds itself at the very geographical heart of this increasingly dense network, as underscored by the establishment in 2024 of political offices by both the Houthis and Hamas in Baghdad.

Amidst this growing Iranian influence, the U.S. footprint in Iraq has been greatly reduced. All non-essential staff at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad were repatriated in 2019, and later that year, the Iranian proxy Kata’ib Hezbollah carried out a series of deadly rocket attacks on U.S. installations in Iraq. Washington responded with several retaliatory airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, culminating in the January 2020 drone strike at Baghdad’s airport that killed Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani, commander of the Quds Force and Iran’s second most powerful figure. The assassination, immediately condemned as an act of terrorism by Tehran, steeply escalated the tension between the two countries; in Iraq, it further inflamed public frustration over foreign intervention and state corruption, in a wave of large-scale protests known as the Tishreen Movement. Under the mounting domestic pressure, the central government vowed to expel all foreign troops from Iraqi soil. Consequently, the first Trump administration began a gradual withdrawal of its troops, transferring control of several military bases to the Iraqi security forces. The U.S. officially ended its combat mission in 2021 under President Biden, while maintaining a small military presence in Iraq in an advisory capacity, currently scheduled to conclude in September 2025. Concurrently, the NATO training mission has been significantly expanded at Baghdad’s request.

Today, Iraq’s economy remains overwhelmingly dependent upon oil and gas. Investment is limited, as large portions of its oil revenues are absorbed by the bloated public sector, which accounts for almost half of the employed population. Many government apparatuses are effectively corruption-ridden fiefdoms, hindering the implementation of desperately needed public reforms.

Iraq ranks amongst the world’s most vulnerable nations to the dramatic effects of climate change. Temperatures are rising several times faster than the global average, and more than half of the country’s agricultural land is deemed to be at high risk of degradation due to restricted water flows along the Tigris and Euphrates. In a country which significantly overconsumes water, undersupply can rapidly exacerbate food insecurity and, indirectly, spark further social unrest. Compounding this issue, nearly three quarters of Iraq’s water flows into the country from Turkey and Iran, both of which are grappling with their own water scarcity and have significantly cut water flow to Iraq. Furthermore, Turkey and Iran’s proxy conflict in Iraqi Turkistan carries the prospect of weaponising water-sharing with Iraq into a political tool.

In an effort to diversify its economy away from hydrocarbons and to strengthen its geopolitical standing, Baghdad is currently pursuing the ambitious Development Road. The project would see a significant upgrade to the Faw port on the Persian Gulf, to be linked by a 1,200-km dual road-rail corridor to Turkey’s transport network. The initial phase of the project is expected to be completed by 2028, at a cost which is widely believed to exceed US$24 billion. Upon completion, the project would provide a new trade pathway from Asia to Europe, cutting shipping times by 10 days compared to the Suez Canal. The Development Road would also compete with several other projects, such as the U.S.-sponsored India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor — which bypasses Iraq via Saudi Arabia and then connects to Europe from the Israeli port of Haifa — as well as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which cuts through Iran before entering Turkey. Success for Iraq’s project depends heavily on external funding from countries such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, as well as on Turkey’s support. Indeed, the Development Road could equally alleviate or aggravate the sensitive issues which have defined the recent relations between Baghdad and Ankara, such as water-sharing and the Kurdish question. Erdoğan’s 2024 visit to Baghdad, the first in 13 years, is seen by some as an important step towards a détente between the two countries. Following the visit, the Iraqi government now designates the Kurdish PKK movement — considered a terrorist group by Ankara — as an illegal organisation, a move which could be part of a broader rapprochement aimed at ensuring the Development Road’s success.

A century after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Iraq remains a land suspended between past empires and future aspirations — a nation at the crossroads of competing powers. Buffeted by foreign interventions, sectarian strife, and the long shadows of dictatorship and war, the Iraqi people have endured immense suffering: cities shattered, lives uprooted, generations marked by conflict. And yet, in the chants of the Tishreen protesters, in the ballots cast by weary hands, and in the daily perseverance of life rebuilt from rubble, there endures a fragile hope, caught between resurgence and relapse, for a more just, accountable, and sovereign Iraq.

47 view(s)

To receive our latest articles as they are published, please consider subscribing to our newsletter — just enter your email address below and click ‘Subscribe’

Leave a reply…